By Thaïs Grandisoli

Deforestation is at a “12-year high” in the Brazilian Amazon and the weakening of environmental legislation is a significant part of the issue, says a new study.

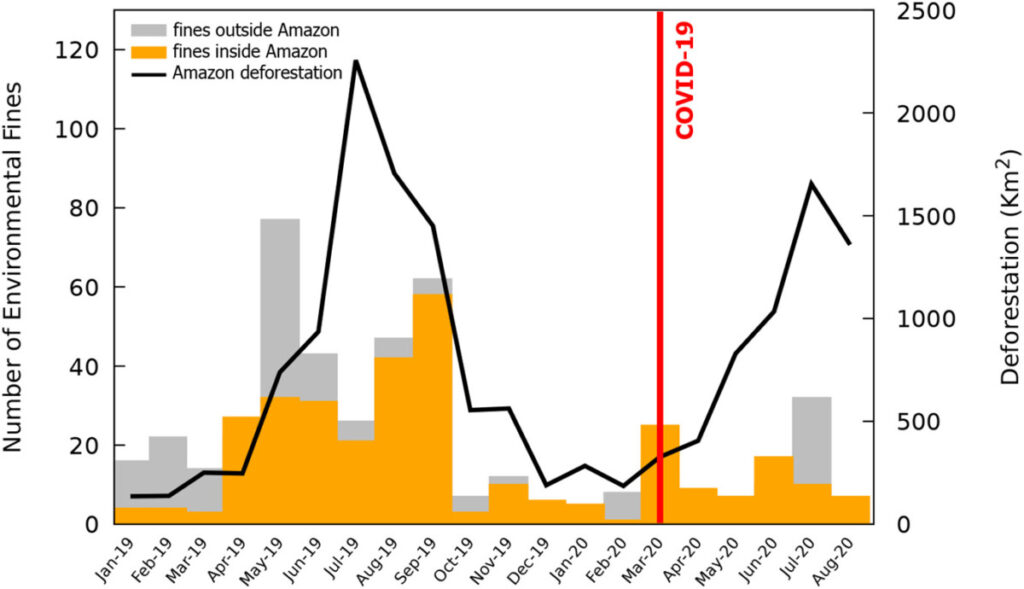

Despite the loss of thousands of square kilometres in the region, the number of fines for illegal deforestation infractions was reduced by 72 per cent in August of 2020 compared to March of that same year, according to the study coordinated by a team of researchers at the Biology Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (URFJ).

“The region has been through a process of deforestation for a long time now,” says Rita Portela, Ph.D. professor at URFJ’s Biology Institute. “But this has recently increased at an alarming pace, especially after the pandemic.”

The lack of enough enforcement and the heavy presence of corruption in law enforcement are known issues affecting Brazil’s situation. The weakening of environmental protection legislation affecting the Amazon only adds to the problem and looks to have long-lasting, even permanent, impacts.

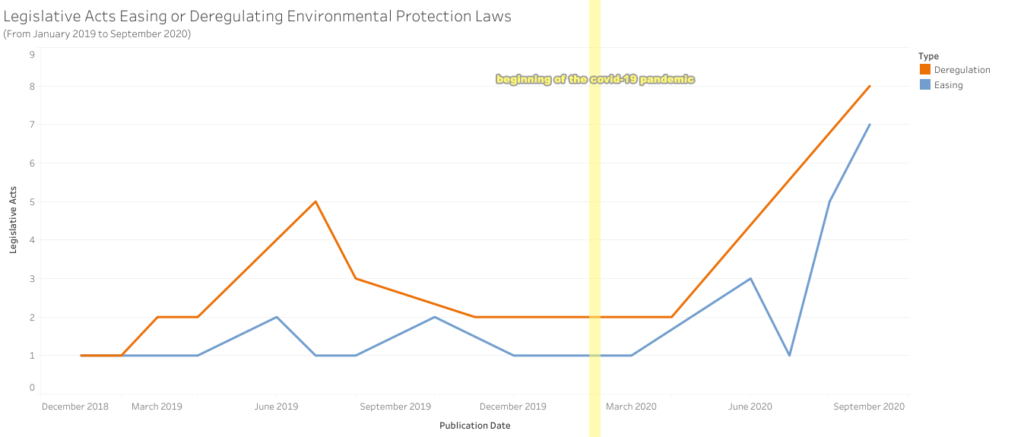

Since the new federal administration took office in 2019, 57 legislative acts were aimed at weakening environmental protection in Brazil. The data also shows how almost half of these acts happened after the COVID-19 pandemic hit that country.

Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far-right leader, took office after a tight election in 2019. He’s been openly critical of government agencies that enforce those laws and has called fines for environmental crimes an “industry” that needs to be abolished.

“With these agencies weakened, the first outcome is an increase in impunity when it comes to deforestation,” says Portela, who coordinated the study that was published in the Biological Conservation journal in January.

Since the pandemic hit the country in March of 2020, these acts started happening at a faster pace.Source: “The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to weaken environmental protection in Brazil” by Mariana M. Vale et all published in the Biological Conservation journal. Photo credit: Thaïs Grandisoli

The Amazon is home to a million indigenous people and immense biodiversity. It plays an integral part in regulating the world’s oxygen and carbon monoxide cycles. As it is the largest remaining tropical rainforest, the Amazon could play a key role in slowing down global warming if CO2 emission levels are controlled in the region.

In November of 2020, Brazil’s space agency INPE reported that the region’s deforestation levels surged to reach their highest in 12 years.

A threat to Indigenous communities

One of the government firms most impacted by recent political measures was FUNAI, a protection agency for Brazil’s indigenous interests. Only days after taking office, Bolsonaro signed a decree that stripped FUNAI of the power of assigning new pieces of land for indigenous communities. That duty was in turn given to the Ministry of Agriculture. The Brazilian Supreme Court later reversed the decision, but evidence shows that deregulation efforts had already had a significant impact on demarcated territory in the Amazon.

There have been active efforts to expand mining activity to indigenous territory in the Amazon region.

“These communities, who are in voluntary isolation after COVID, are trying to prevent contamination,” says Portela. “Not to mention the destruction in the biodiversity of their land.”

The fines refer to illegal deforestation acts committed elsewhere in Brazil and compares to those within the Brazilian Amazon. The vertical red bar shows the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in Brazil (March of 2020).Source: “The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to weaken environmental protection in Brazil” by Mariana M. Vale et all published in the Biological Conservation journal. Photo credit: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108994

According to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, the largest remaining territory in the world still under Indigenous jurisdiction is located in the Amazon. For many of these territories, the challenging geographical access could cause even more disastrous consequences if COVID keeps spreading. FUNAI has reserved about 13 per cent of territory in the Amazon region for Indigenous people. Besides the constant illegal attacks on this land, the weakening of environmental protection legislation and government agencies could cause further devastation of the environment — and more deaths.

Célia Xakriabá, an Indigenous activist and educator in Brazil, is one of the most influential voices speaking on the issue. In an interview with the Guardian in August of 2020, Xakriabá explained why environmental destruction, including fires, is a dangerous threat to the lives of thousands of Indigenous communities who live in the Amazon.

“When the forest is burning, the birds and the animals are either burned, or they go away. And this doesn’t affect only the animals, but it also affects us. We rely on them to eat,” Xakriabá told the Guardian. “So with no animals, we have to rely on food from the outside, and this ends up making our children and our women sick.”

This issue is highlighted now during the COVID-19 pandemic, where Indigenous people have been disproportionately hit. According to the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, which tracks and advocates for the country’s Indigenous political movement, there have been 50,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 900 deaths among Indigenous communities. The number of people infected is over five per cent of the entire Indigenous population in the country. Aruká Juma, the last male leader of the Juma people, died due to COVID-19 complications in February.

The urgency to take action

In April of 2020, footage of a ministerial meeting released by order of the Brazilian Supreme Court showed Brazilian Environment Minister Ricardo Salles confirming the causal link between the pandemic and the dismantling of environmental protection laws. The minister reminded other administration members that the media’s attention was almost exclusively on the COVID-19 pandemic. Salles then suggested they take advantage of this “tranquillity” they were experiencing to act in favour of weakening environmental protection laws. “We should open the flood gates, change all the rules and simplify norms,” said Brazil’s Environment Minister.

“The people who were appointed as officials don’t even have the appropriate knowledge or the background to be holding these positions,” says Paula Onofre, a Brazilian Ph.D. biologist who works in Toronto for a company in the biogenetics research area.

Onofre was responsible for organizing the protest in front of the Brazilian consulate in Toronto in September of 2019. The biologist publicized the event on Facebook, and even on short notice it gathered over 40 people demanding a stop to deforestation in the Amazon.

“I want to be an example to my children who were there protesting by my side,” said Onofre, “I don’t have any authority on the matter, but as a responsible citizen, I can voice my concerns.”

Onofre says she prioritizes teaching her children about the importance of taking care of our planet, but she explains this shouldn’t be only the responsibility of younger people. The biologist said ever since she arrived in Canada, she has met people who were incredibly receptive to the cause, even though they didn’t always know how to help.

“I haven’t been protesting in a while because of COVID, but I think it’s essential that people use this time to seek out information,” she says.

Onofre says she was also contacted by Canadians who wanted to help organizing the event. “There weren’t only Brazilians present, and as time went on, more pedestrians stopped and joined too,” she adds.

The NGOs acting in the Amazon

Non-Governmental Organizations, or NGOs, have also faced increased difficulties when acting in the Amazon region, with many ceasing or indefinitely pausing their activities since 2019. Carla Zambelli, an open critic of NGOs, was appointed by President Bolsonaro and Environment Minister Salles as the president of the country’s environment commission earlier this month.

The projects and declarations currently overseen by the commission suggest that their current intention is making alterations to categories of protected areas in order to facilitate economic exploration, thereby reducing the size of those areas.

NGOs are active in the Amazon region in multiple ways but are generally focused on concerns related to the destruction of fauna, flora and the threats to Amazonian Indigenous communities. To expand their ability to act, these NGOs often partner up with government agencies, and with those weakened, the NGOs are also seeing their activities being limited.

In November of 2019, the State of Para’s police arrested four volunteer firefighters working for a smaller NGO from Alter do Chão. They were charged for the very fires they were attempting to contain, and the case only served to add more pressure for other NGOs acting in the area, especially smaller ones.

This case gained significant attention from the media at the time. The members of the group arrested had their heads shaven and their pictures publicized quickly after.

“Maybe WWF [the World Wildlife Fund] isn’t as scared because they’re a well-established international organization, but this certainly serves to discourage the work of smaller NGOs who are working from the frontlines in the Amazon,” says Portela about the event.

Bolsonaro had claimed the WWF was the one responsible for financing the Amazon fires and even accused Hollywood actor Leonardo DiCaprio of contributing money specifically to that purpose. The NGO quickly denied all of those allegations, including that they received donations from the actor. DiCapiro later released a statement saying that he’s in full support of those working alongside NGOs to stop the rainforest’s further devastation.

Portela says media coverage has been essential in bringing these issues to the public’s attention. The pandemic should not be seen as an excuse to put this coverage on hold, she says, as the evidence suggests that Brazil’s current health crisis only serves to add more urgency to the problem.

Besides increasing media attention, new international pressure could also serve to slow down plans to implement further devastating measures.

Attention from concerned citizens from all around the world is also crucial in tackling the issue.

According to Onofre, who resides in Canada, she plans to continue being outspoken on the issue. “They need to know the whole world is watching,” she says.

Featured photo credit: Unsplash

Updated, March 30, 2021: A previous version of this article misspelled Rita Portela’s name.