By Hansil Mehta

The implications of Myanmar coup are worrying for Rohingya living in Myanmar as they are at a heightened risk of repression, says a human rights expert.

The director of the Human Rights Research and Education Centre at the University of Ottawa, John Packer says, “There is now almost no constraint on the military.”

Packer says the act of coup in the Burmese capital Nay Pyi Taw last month wasn’t surprising and the military had indicated it a few days in advance.

“This was unusually kind of telegraphed coup,” Packer says.

This is the third time in Myanmar history the army has seized power of the country after a coup in 1962 and annulment of the election in 1990.

After decades of military rule, a new constitution was created in 2008 and later the country transitioned from military rule to democracy.

Saifullah Muhammad, a Rohingya living in Canada, says the constitution allows the military to take power.

“First when I heard the word coup, I thought that it was misleading because according to 2008 constitution, the military is legally entitled to take over the government,” Muhammad says.

Muhammad says article 419 of the 2008 constitution gives the commander-in-chief of defence services power to take over the government.

“We must look critically at the constitution itself, and how it was written to empower the military regime and support their aims,” Muhammad says.

The army, which is known as Tatmadaw, declared the 2020 Myanmar general election results illegitimate and arrested State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League of Democracy claimed victory in the November 2020 election after retaining control of the parliament.

A Nobel Peace Prize winner, Suu Kyi has widely been seen as a controversial figure in the past decade.

Suu Kyi’s term as Head of State escalated the persecution of Rohingya people, which the House of Commons unanimously declared as a genocide in 2018.

The Rohingya are a native ethnic and religious minority mostly located in the Rakhine state of Myanmar.

“Not only the government facilitate 2017 genocide campaign, but Suu Kyi also condoned and defended the military actions,” Muhammad says.

More than a million Rohingya have been forced to flee their land and country since 1980s.

Muhammad fled to Bangladesh at the age of five where he studied in a refugee camp. He later came to Canada in 2016 after spending 10 years in Malaysia.

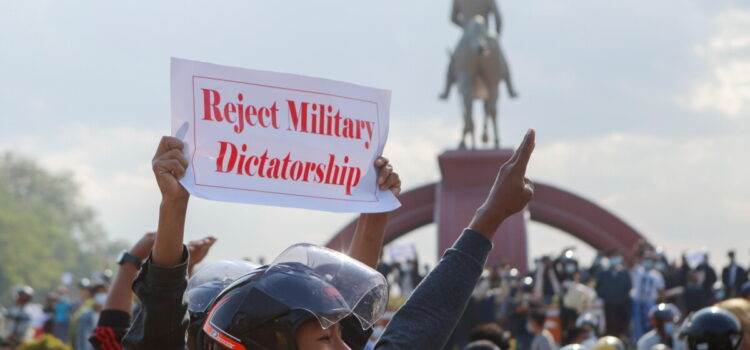

The coup was followed by widespread protests throughout the country.

Burmese people are calling for Aung San Suu Kyi’s release and transition to democracy.

Muhammad, on the other hand, says there was nothing to gain for Rohingya people even if the democratic transition happens.

“The democracy in Burma under the Aung San Suu Kyi governments from 2011 to 2021, that democracy presented the Rohingya people three genocidal attacks in 2012, in 2016, in 2017,” Muhammad says.

He says the democracy people in Myanmar want restored is a shaky democracy.

The current constitution does not recognize Rohingya as citizens of Myanmar, hence barring them from the right to vote among many other rights.

“As a Rohingya, we are looking for a true real democracy to be implemented in Burma,” Muhammad says.

Packer says there is a clear opportunity for a better democracy based on human rights and justice as the majority of Burmese people are against the army on the streets.

“The military had been rehabilitated under Aung San Suu Kyi, who was elevating them to kind of defender of the nation and so forth,” Packer says. “That’s clearly now more than in question.”

Packer says the young generation in Burma is calling for better democracy and better human rights.

“Part of the young generation is also calling for restoration of Aung San Suu Kyi,” Packer says. “But broadly, all the groups are saying, the bottom line here is a better system, a more genuinely democratic one.”

Muhammad says he hopes for the military rule to end soon with sanctions and pressure from the international community.

“I do believe that as young generation in technology times, maybe the military messed up with the wrong generations,” Muhammad says.

The international community’s response to the coup has been polarizing.

China, for instance, has described the coup as “a major cabinet shuffle.”

China and Russia blocked UN Security Council’s attempt to officially condemn the Myanmar coup.

On the other hand, Canada and Britain have slapped new sanctions on Myanmar and the U.S. government has been vocal on the issue as well.

Packer says Canada has to be true to its values and declarations to influence in this matter.

“It can act with integrity, it can follow its actual international obligations, for example, standing up against genocide against the Rohingya,” Packer says. “It can actually work through not only some allies, but also others, like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and many others with the OIC.”