Rising prices at local thrift stores are shocking customers

CanadaEtobicokeLifestyleNewsToronto Apr 9, 2024 Adrien Glazer

Shopping at thrift stores is meant to be an accessible alternative for those who might not be able to afford regular retail prices, but at some big thrift store chains, customers are wondering if maybe they’re no longer getting a bargain.

Savers — known in Canada as Value Village — is one of the largest thrift store chains in North America. They have over 300 locations, with 140 of those locations in Canada, and 74 in Ontario.

Value Village operates on a donation based model. The company accepts second hand goods from consumers, and some from local non-profit organizations. The organizations are paid a flat rate for their goods, which Value Village then turns and sells for profit. This is unlike other thrift chains – like Goodwill and Salvation Army – where a bulk of profit goes to supporting local charities and non-profit organizations.

Value Village is a publicly traded, for-profit model business, with U.S. private equity firm Ares Management as a majority shareholder.

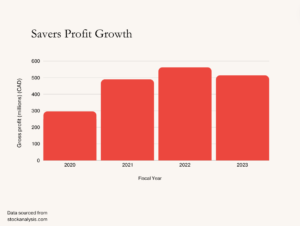

With the rise in popularity of thrifting in recent years, Value Village has seen an overwhelming increase in profit. From 2020 to 2021, the Savers company saw an almost 45 per cent increase in gross profits.

A bar graph showing the profits of Savers Value Village from the past four years Photo credit: Adrien Glazer

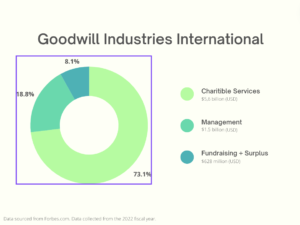

Meanwhile, competitors like Goodwill circulate the bulk of their profits back into the company and local community. A financial report from Forbes says that in 2022, Goodwill Industries International saw $7.6 billion in total revenue. However, around 74 per cent of that revenue went to charitable services, with the remaining 26 percent going to management of the company, fundraising, and surplus.

A circle graph showing what funds from Goodwill Industries profit is allocated to Photo credit: Adrien Glazer

One of the biggest changes that consumers have been noticing recently is a significant increase in prices. With the increase in popularity, and with Savers operating on a for-profit model, it’s not surprising that the company has increased prices to increase profit based on demand. But still, these price hikes have caused outrage among consumers at one local Etobicoke location.

Mika Soetaert is a fashion student studying at Toronto Metropolitan University, and she is also an avid thrifter who often commutes out of the city to shop at larger locations. She is a frequent customer of the Value Village location at Islington Ave. and Titan Rd., and she’s not too happy about the recent increases.

“The more charitable thrift stores have raised their prices less so than Value Village, places like Salvation Army and Goodwill, I have found they haven’t raised their prices as much. I’m not sure how much of that is to compete with inflation, versus how much of that is tied to the whole gentrification of thrifting. It’s more Value Village that I have a bone to pick with,” says Soetaert.

She started thrifting the majority of her wardrobe in the winter of 2018. As a fashion student who focuses on sustainability, she does this to avoid buying fast fashion first-hand to lower her own ecological footprint, though she says that this likely isn’t the same for everyone, and that major chains like Value Village have caught on to this.

“Now [that] there’s a lot of young people that don’t thrift out of price necessity and thrift because it’s cool, that does increase demand,” says Soetaert. “So then they increase the prices, but it’s more so that they’re increasing the prices because they know people will come thrifting regardless of if garments cost seven dollars on average, or if they cost 14 dollars on average. So, they will charge 14 [dollars] because they can.”