COVID-19 highlights need for race-based health data in Canada

COVID-19HealthNews Mar 2, 2021 Tatiana Furtado

By Tatiana Furtado

Advocates and healthcare workers across Ontario are making a strong case for the collection and publication of more race-based health data after COVID-19 helped uncover inequities in the healthcare system.

“The current pandemic has opened up eyes to a lot of things we still need to do. We need to have race-based health data to support what we’re working towards. It’s difficult to help your own community when you don’t even know the severity of it,” said Ken Noel, president of the Walnut Foundation, a non-profit organization that assists men in the Black community to seek support and guidance regarding their health.

Noel believes the healthcare sector must publish health data not only to support Canadians, but to help doctors effectively do their jobs too.

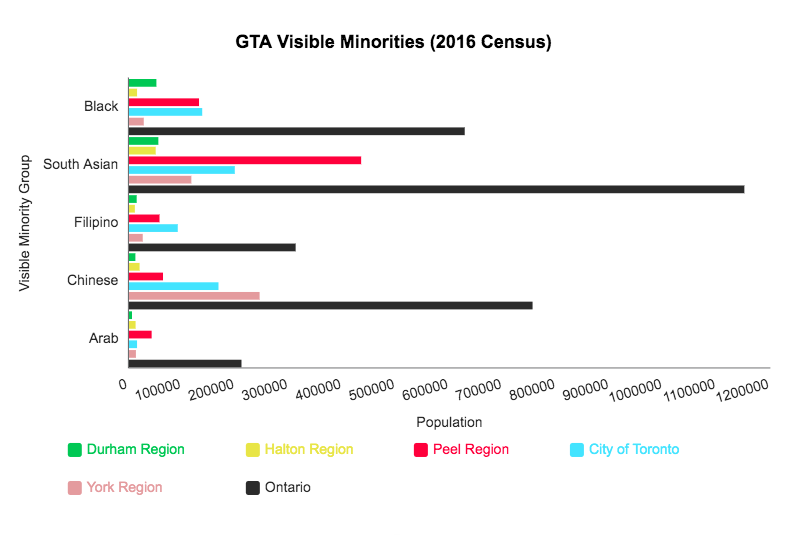

Statistics Canada uses the term “visible minority” to define population groups, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour. The number of visible minorities in the Greater Toronto Area compared to the leading causes of illness and death shows regions with higher visible minorities consistently face more health concerns.

Data shows the total population of the top five visible minority groups: Black, South Asian, Filipino, Chinese and Arab in the regions of Durham, Halton, Peel, City of Toronto and York.

According to the 2016 Statistics Canada Peel Region census profile, the non-visible minority population was 518,080, overpassed by the visible minority population of 854,565. A 2018 City of Toronto report showed the total population to be 2,956,024, while the visible minority making up 1,522,352, or about 51 per cent of the population.

The City of Toronto and Peel Region are both heavily populated and visible minorities account for over half of the population. Developing race-based health data will support these communities and their challenges.

Dr. Nadine Furtado, Associate Clinical Professor and Head of the Ocular Disease and Imaging at the University of Waterloo School of Optometry and Vision Science was a guest speaker at a Walnut Foundation seminar earlier this year. She covered the topic of eye health and the conditions of glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy, which tend to be most prevalent in the Black community.

“There is a growing awareness about the importance of collecting race-based data to better understand patient diversity and the inequalities which exist within our healthcare system. The lack of this data can actually make it easy to overlook these issues and not fully appreciate how they impact the health of an individual,” she said.

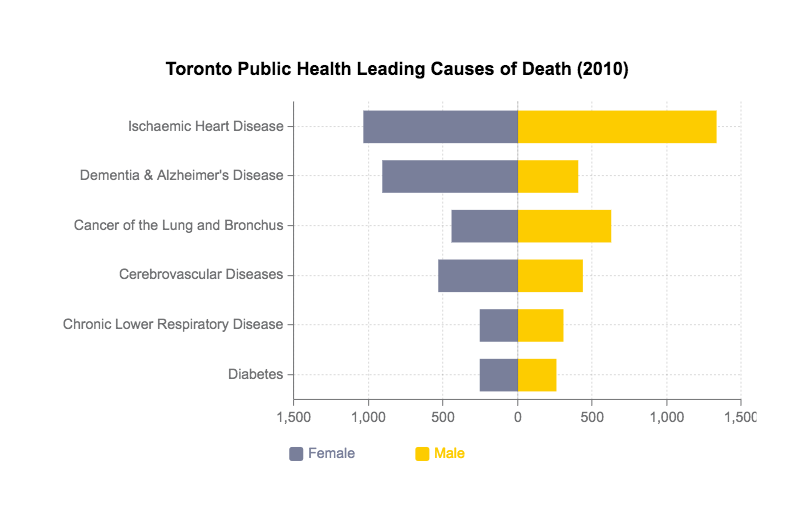

In 2010, Toronto Public Health released a report showing the leading causes of death in the city. The top causes included heart disease, Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory disease and diabetes.

But without race-based data, there are not enough details as to who is being affected by these illnesses and it makes it difficult to determine which populations need more help. Doctors like Furtado are helping raise awareness of the need to show which communities are more at risk.

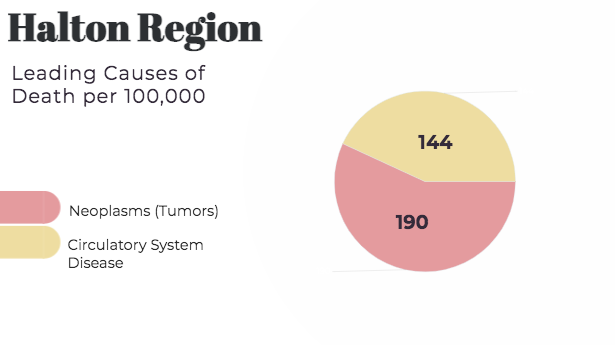

Halton Region has a visible minority population that is significantly lower than that of Toronto or Peel. In 2016, the population of visible minorities was only 138,995, while the non-visible minority was 401,980. Halton’s 2015 Mortality Report showed there were only two prominent causes of death: tumors and circulatory system diseases.

Halton Region’s 2015 morality report shows the top two leading causes of death. Photo credit: Tatiana Furtado

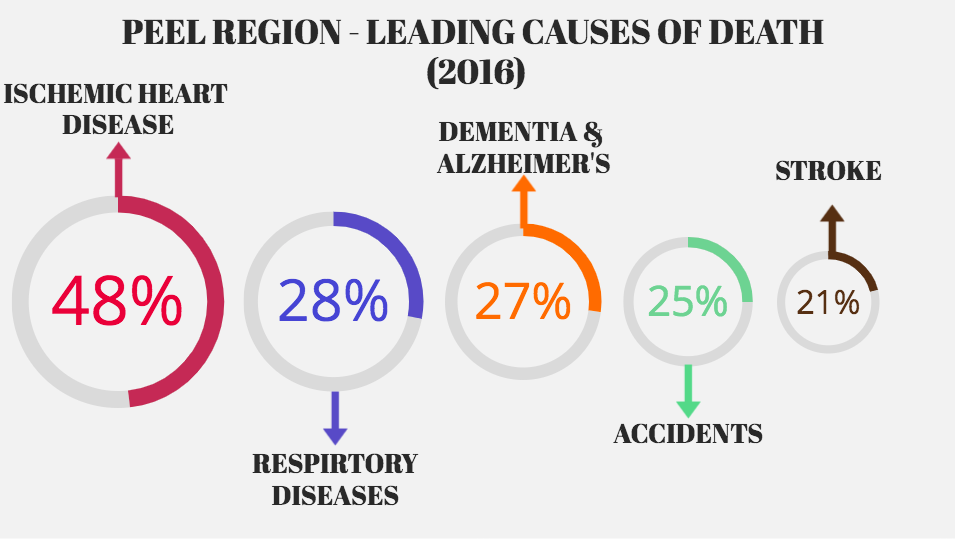

In comparison, the data published by Peel Region in 2016 shows many more leading causes of death.

The 2016 data suggests a major difference between these two regions, with the region with more illnesses also being home to more visible minorities. More up-to-date and race-based data could provide further insight into this disparity.

“To effectively monitor health inequities, we not only need data about health and health care, but also information about patient demographics,” Dr. Furtado said.

Dr. Danny Vesprini, a radiation oncologist at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre focusing his research on cancer genetics and people at high-risk for prostate cancer, has developed the MORE program to help research the BRCA1/2 mutation gene that is prevalent in Black Caribbean men.

He’s found the lack of race-based data is also influenced by cultural and socio-economic barriers. Dr. Vesprini refers to it as, “a culture of not trusting establishment.”

“If there was more genuine research and concern about people in these communities, then that culture would start trusting the medical community and see that we’re trying to improve things,” he said.

Systemic racism has caused people in the Black community to not trust medical advice, making them less likely to engage in research that would contribute to creating data that medical experts refer back to.

“Wherever you see there is a lower socio-economic group, there is always going to be more illness because they have less access to healthcare and healthy living. All the systemic racism over the years has placed them in that category,” he said.

Dr. Vesprini sees it as a cycle. Visible minorities do not trust medical professionals because they do not see themselves represented in the field. He says in order to change this cycle we need to teach people from these minority communities at a young age that healthcare professionals are on their side and create a culture that encourages Black men to go into the field themselves.

The Walnut Foundation is working with Dr. Aisha Lofters from the Women’s College Hospital at the University of Toronto to develop race-based data, with a particular focus on prostate cancer rates for Black individuals compared to other groups.

The hope is that organizations working together with researcher scientists will lead to better advocacy for change.

“Healthcare and health outcomes among racialized groups are understudied in Canada. We can’t address racial and other disparities if we don’t first study where they do and don’t exist… We can’t just rely on data from other countries,” Dr. Lofters said.