Why victims of assault can’t say no — and can’t speak up

CanadaHealthNews Apr 13, 2021 Saloni Bhugra

By Saloni Bhugra

Low rates of reporting sexual assault are tied to societal power structures that normalize abuse, experts say.

According to SexAssault Statistics Canada, only six out every 100 sexual assault incidents are reported. And those that do come to light often lead to blowback against the victim.

During the #MeToo movement, for example, allegations by a woman using the pseudonym Grace against actor Aziz Ansari led to media reactions some saw as victim blaming.

Caitlin Flanagan of The Atlantic wrote about Grace’s inability to react immediately, saying previous generations of women were better at avoiding incidents. “But as far as getting away from a man who was trying to pressure us into sex we didn’t want, we were strong,” she wrote.

Bari Weiss, then a writer for The New York Times, asked why Grace didn’t leave, “If he pressures you to do something you don’t want to do, use a four-letter word, stand up on your two legs and walk out his door,” Weiss wrote. She also listed things victims should do if they don’t want to get assaulted: “If you are hanging out naked with a man, it’s safe to assume he is going to try to have sex with you.”

But experts reject this kind of advice as potentially dangerous. More than 11 per cent women who are victims of assault are seriously injured, points out Harshita Chhatlani, the founder of The Safe Space Project, an organization aiming to create a virtual safe space for victims of sexual and physical assault by providing people with mental and legal aid.

“When you are on the receiving end of abuse, more often if not you respond with flight, fright or fight. For women, you are in a position where someone more powerful than you have control, so it’s often fright/freeze, where you want to protect yourself and your body, so you comply,” Chhatlani said.

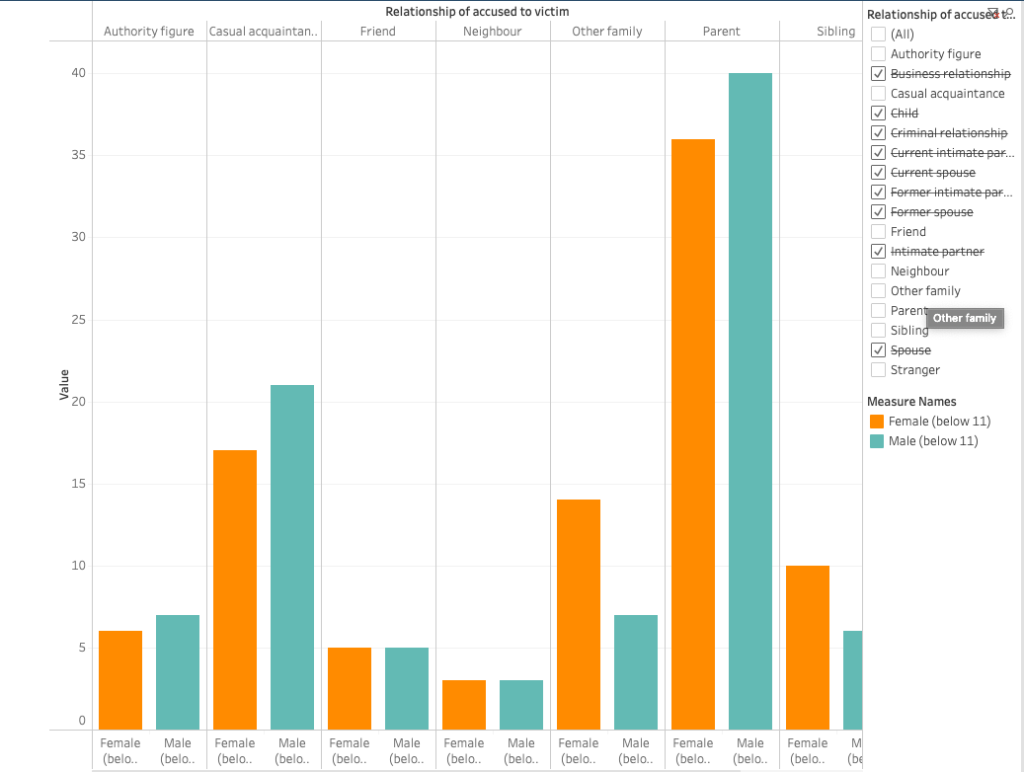

According to the 2014 General Social Survey Canada, one in ten Canadians have faced physical abuse before the age of 15, and 70 per cent of which have also witnessed sexual assault, and many will have repressed memories.

“Through repression, your brain saves itself from the nervous breakdown that will follow right after, … when I’m still in therapy I realize I have memories of abuse from my childhood that are repressed because my brain didn’t have the capacity to understand what was going on,” Chhatlani said.

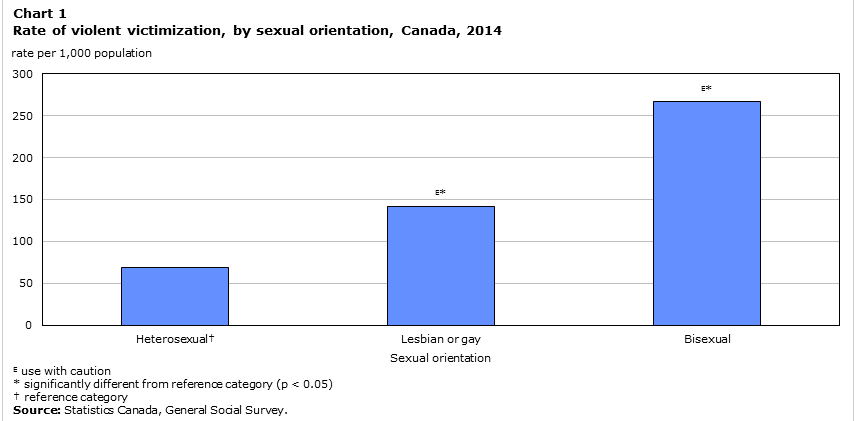

For some, the rate of abuse is even higher, Statistics Canada reports that one in five people from the LGBTQ+ community faces violent victimization, which includes sexual assault, robbery and physical assault.

“Gender identity plays a role in experience, even though people from all genders experience shame and guilt while reporting their abuse, the LGBTQIA+ community faces it the most, followed by females and then males,” said Purwai Pravah, a counselling psychologist and a suicide prevention specialist. “Many friends from the community have shared that they were made fun of, their identity was named as fake and were called attention-seeking, or that they called on for abuse by the way they behave, dress, etc.”

According to StatsCan, about 35 per cent of men 15 years or older face sexual or physical violence at least once.

“For men, it’s hard to speak up because it becomes a matter of pride, followed by a lot of shame from society. The fact that men are abused too is far from acceptance in our society,” Pravah said.

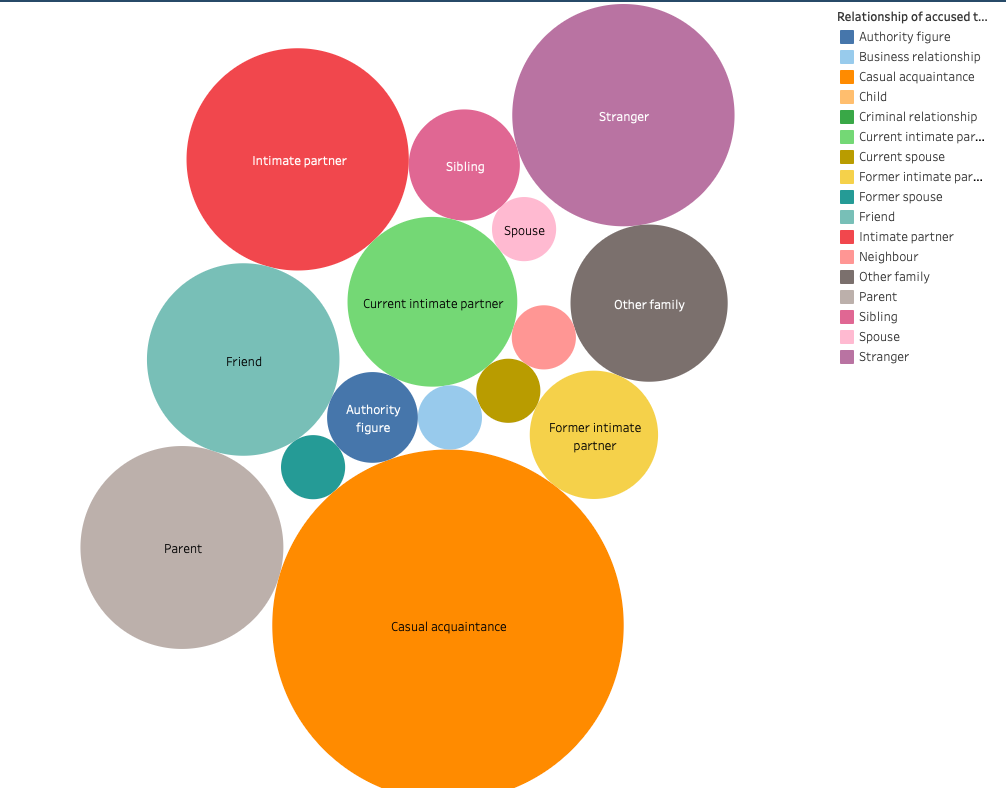

In 80 per cent of Canadian cases the assailant is known to the victim or is a family member. Pravah said that in situations where the victim is dependent on an abuser for food and shelter, it is nearly impossible to take a step toward reporting or getting help.

“There is a concept of learned helplessness in psychology, which is basically [how] after going through a difficult situation, again and again, you begin to accept it, you agree with being helpless,” she said.

Canada’s Department of Justice published a report on sexual assault crimes that included statistics and a survey by Violence Against Women Survey (VAWS) which showed that 29 per cent of married women face marital rape, out of which 39 per cent are disabled women.

Chhatlani said it is hard for victims to speak up because of the fear that they will be banished, thought of as victims, or that they simply won’t be believed.

“To talk about this and be met with accusations of lying, is very sad,” Chhatlani said.

According to SexAssault cases only two to four per cent of all cases are false accusations.

Chhatlani said it speaks volumes about ingrained societal attitudes that in many countries marital rape is still not even criminalized. “It’s as though once you’re married, your body and bodily autonomy is automatically his,” she said.

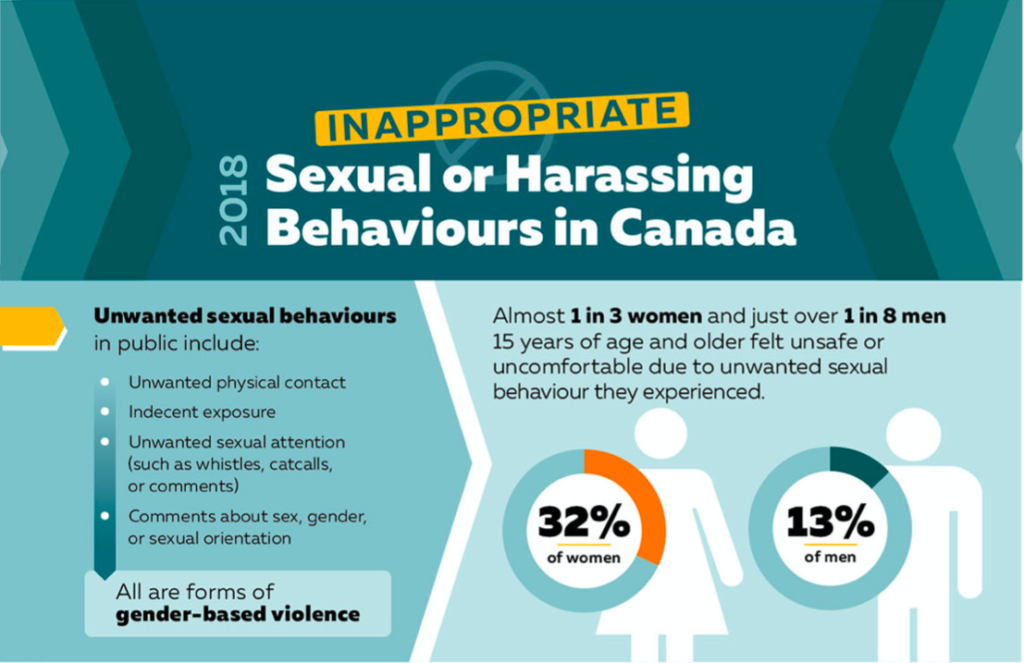

A 2018 report on sexual harrassment revealed that 32 per cent women and 13 per cent men face sexual harassment in public. Most of which, again, go unreported because of normalization of such acts.

Normalization is also often the root of inability to identify abuse. Chhatlani said that we’re often made to think that “at least he didn’t touch you (in case of harassment), at least he didn’t rape you (in case of molestation), it’s just a slap — it happens.”

Chhatlani and Pravah agree that one of the major causes of trauma and the inability to speak up is the normalization. Pravah said that conforming to gender roles might also be a reason that young girls and boys internalize trauma.

The roots, Chhatlani says, are in societal power structures. “It’s pretty straightforward that the group in power is cishet men and speaking against power is a tough job — you don’t get much support.”